Inside Higher Education Faculty Attitudes Survey 2017: An Abrupt About Face

November 7, 2017 – Peter Shea

For several years the publication Inside Higher Education has been conducting surveys of faculty about technology. An interesting aspect of this work has been a section about faculty attitudes toward online learning, especially perspectives on whether online education can achieve outcomes equivalent to classroom education. As noted elsewhere on this site, this is not a question that has been left to speculation. At least 14 meta-analyses have concluded that outcomes on all measures considered across thousands of studies (spanning decades) find equivalence between online learning (or distance education) and classroom education. The high level finding seems to be that the success of instruction is not a modality issue, but rather an issue of design.

So it is somewhat curious to find profound skepticism on the part of faculty when they are asked whether for-credit online courses can achieve student learning outcomes that are equivalent to those of in-person courses. The literature says “yes”. But, until this year faculty have said “no”. Lets take a look at the last 5 years of studies.

Back in 2013 Inside Higher Education collected data from 2251 faculty members. The study did not report on response rate, so we don’t know exactly how many instructors were in the total sample versus how many responses were received. There were also no attempts to weight responses such that they might reflect the profile of faculty nationally from and there are caveats to that effect in the brief methodology sections of the reports for certain years.

Putting that to the side for the moment, the 2013 surveys finds pretty deep doubts on the part of faculty about the implied quality of online education. Faculty were asked to respond to the following question: “Online courses can achieve student learning outcomes that are at least equivalent to those of in-person courses in the following settings: At Any Institution”. Across the sample only 21% of faculty expressed some form of agreement. About a third were neutral and close to 50% disagreed. Among faculty who had never taught an online course the skepticism is even greater. For example, in the 2013 survey only 3% of faculty express strong agreement that online and classroom instruction produce the same student learning outcomes.

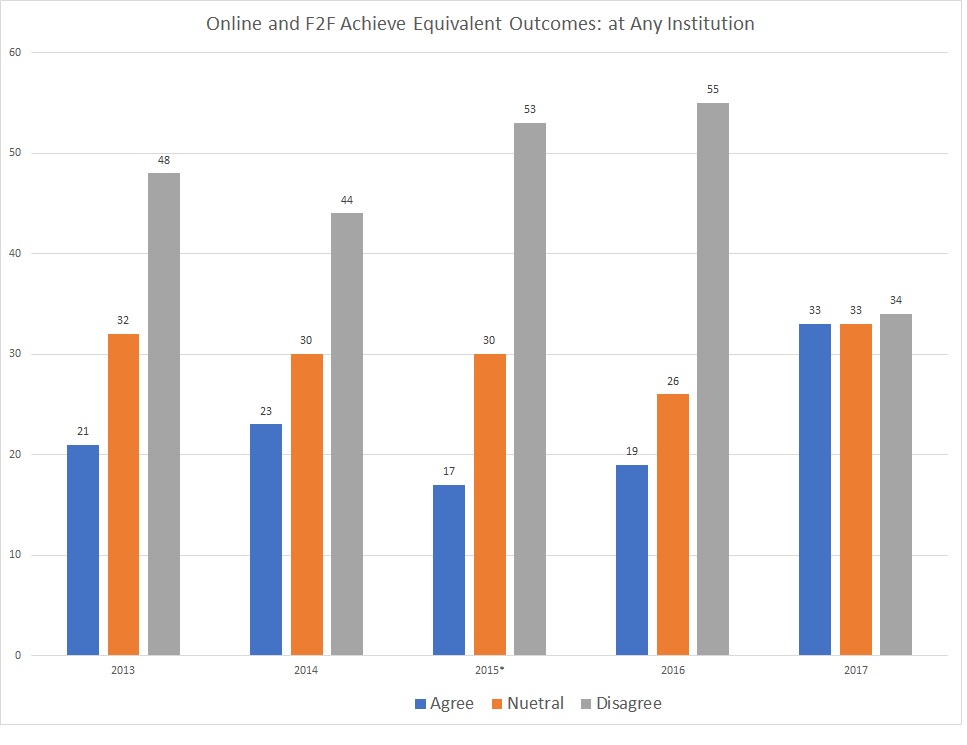

These findings are pretty consistent in the four years in which data were collected from 2013 to 2016. From 2015-2017 statistical weighting was conducted and response rates were reported so we can have somewhat more confidence in these studies. What is somewhat shocking is the 2017 survey findings. Suddenly, this year, faculty have done an about face. For the sake of simplicity I summarized findings across studies for the last five years, lumping agreement levels into just three categories. See the results below:

For the three years from 2014 to 2016 faculty expressed growing doubt about equivalence of online and in person courses with increasing numbers indicating disagreement (in gray). But in 2017 all that changed. Suddenly faculty are evenly split on whether online and classroom instruction are equivalent. What accounts for this change? It would be instructive to hear more from the authors of the report. The 2017 report itself doesn’t mention the big turnaround, though there is some mention of possibilities in an IHE article. These shifts are really unusual. We should be digging deeper to understand what happened.

We can have poor design in the classroom and poor design online, so, in the meta-analytic literature we have many studies finding that online outcomes are worse and many studies finding classroom instruction is worse. We can also have good design in classrooms and good design online, which accounts for the equal number of studies finding that online is better and that classroom is better. What is really a mystery is how faculty could change their minds about the equivalence of outcomes so dramatically in a single year.

Older Posts…

The UDACITY San Jose State Experiment

August 30, 2013 – Peter Shea

The recent experiment by Udacity to deliver for-credit college courses at SJSU via their MOOC platform was widely seen as less than successful. Students in the courses performed at much lower levels than their classroom counterparts. The program was briefly suspended while the company made revisions.

The strength of MOOCs to date has been in bringing college courses to hundreds of thousands of students, online, for free. The Udacity experiment at SJSU did two of the three of these differently. The courses were smaller than normal MOOCs and they were not free.

Udacity’s leader, Sebastian Thrun explained the initial poor results in light of the student population that was served, consisting of a balance of high school students and matriculated SJSU students. The source of the poor performance, presumably, was the less prepared high school segment of the population enrolled in the courses. This is the implication at any rate.

The news out recently is that the experiment was restarted over the summer and the results are much better. The SJSU students who took Udacity summer courses through the MOOC platform did as well and in some cases better than the on-campus students in equivalent courses. There is a catch though. This time the courses were open to anyone and fully 50% of the students already had a college credential of some sort. More than one in four had a bachelor degree. One in five had an advanced degree, either at the Masters or Doctoral level.

While I think we must applaud the work being done in the MOOC movement (millions of students getting access to college lectures, materials, and discussion opportunities) we also need to look closely at the results of the emerging movement to use MOOCs to solve major challenges in higher education. The SJSU pilot was meant to help alleviate the bottleneck of wait-listed students without access to traditional college coursework in the California system.

The students in the lackluster Udacity spring pilot may have been somewhat under prepared (though its not entirely clear that they were so different from other SJSU freshman in that respect). The students in the Summer pilot seem skewed in the opposite direction. Its unlikely that we’d find such a high percentage of degree holders in an undergraduate entry level course as found in the summer pilot . The better results in the summer session are likely attributable to this more qualified group of participants*.

We also need to be conscious of the longstanding efforts that have been underway in “traditional” online learning. As Udacity retools their efforts to improve performance the company is adding the resources that have long been recognized as essential in traditional online environments. More human support staff and more interaction with professors are at the top of the list. As MOOCs are increasingly used to solve the issues of access in higher education, they begin to look more and more like regular online courses. This is a good thing. Because regular online courses work well in higher education. We will need to stay tuned as additional results are released. But it is a bit premature to conclude that MOOCs, at least in their original format, will be the solution to the access issues confronting the California system of higher education.

* It would be very useful to have a more granular perspective of just who succeeded as well. What percentage of the SJSU summer pilot students who passed were high school students? What percentage already held advanced degrees? We don’t seem to have those answers yet.

More on the Udacity SJSU pilot can be found here.

Understanding the Effectiveness of Online Learning: The Trouble with Experimental Research

March 25, 2013 – Peter Shea

William Bowen had a piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education recently (see Walk Deliberately, Don’t Run, Toward Online Education).

Having conducted research on the subject for more than a decade I can comment on Bowen’s complaint that online learning is not well understood. He reasonably laments the fact that there has not been much “gold standard” research, i.e. randomized trials with their attending experimental and control groups. This medical analogy highlights a core misunderstanding of the “treatment”. Online learning, in its traditional form, was not meant as an instructional intervention designed to cure a learning problem, but rather as

an intervention to address an access and choice problem. Essentially, traditional online learning in higher education (frequently with the backing of the Sloan Foundation’s Learning Anytime, Anywhere Program) was meant to bring the university with its credentials to a much wider audience conveniently and without the bad “side effects” of reduced learning outcomes. The Sloan Foundation invested about $70 million to achieve this and succeeded spectacularly in the goal of increased access and the broad consensus is that this was accomplished with “no significant differences” in learning outcomes. Currently 6.7 million college students take fully online credit bearing courses (close to zero of these enrolled in MOOCs). That is almost one in three of every college student in the United States.

The problem with the use of a medical analogy is that when the treatment is “choice” randomized experiments undermine the treatment itself. You can’t assign student to an intervention s/he does not want when the intervention is choice over where, when, and how they attain a degree and still actually provide the treatment. The results can’t be valid or reliable so randomized experimental trials are an incompatible research method.This may sound paradoxical, because it is. Ithaka, of which Bowen is founding chairman, has run into this problem itself when attempting to research online learning. Others will as well. One of the new mindsets that we need, along with those advocated by Bowen, will be an acceptance of other research methods that investigate the effectiveness of online learning without interfering with the “active ingredients” of flexibility, convenience, and choice so clearly needed by 21st century learners.

A Rant about Tom Friedman’s Recent NYT Piece

March 5, 2013 – Peter Shea

Tom Friedman has an article in the New York Times about the recent conference convened by MIT and Harvard. The conference title was somewhat ominous: “Online Learning and the Future of Residential Education”(reading between the lines one might wonder if residential education has a future).

Friedman’s article is instructive in several ways, primarily in how the learning sciences have been ignored by elite colleges and by journalists. The irony is rich. While the cry to replace the “sage on the stage” with a “guide on the side” is so longstanding in education that many of us can’t recall when it started, the MOOC/Flipped Classroom movement suggests it was just discovered. What do MOOCers want to do though? Create an even bigger stage – a world-wide stage upon which they can be sage! This ego-driven movement has the potential to set higher education back centuries.

The Flipped Classroom is the latest corporate buzzword that either cynically or unknowingly reflects recommendations from the learning sciences that were already more fully articulated decades ago. What if students read the text before class? What if we promoted more active learning in the classroom instead of lecture? What if we tried to make the class more student centered? Why do we pretend this is innovation?

Why is “watching the online lecture” such a privileged occasion for learning suddenly? One possibility: it generates more “views” for the emerging web-celebrity faculty at elite institutions. Lectures are bad. Unless, as Friedman suggests, they happen in a packed Korean sports stadium. Then they are good. If the goal is fame I mean. What better place to get famous? A sports stadium for faculty! Hurray!

The MOOC movement is, in many ways, regressive, self aggrandizing, and in the end a slap in the face to educators everywhere.

2 Responses to Online Learning Blog